Four City Hall officials assembled at the front of the meeting room in the Wauwatosa School District's Fisher Building for a presentation on Sept. 16, led by Deputy City Administrator Melissa Cantarero Weiss. She opened her remarks by stating the obvious.

City officials are not educators.

Instead, Weiss said, she and other city leaders have experience with facilitating redevelopment of under-used properties, working with developers, growing the tax base and addressing traffic challenges. And they may be able to help the school district as it looks to an uncertain future.

"We're not here with any recommendations for you. That's not our area of expertise," she said. "But we are here to offer you some information."

The city officials' audience was a committee of about two dozen parents of school-age children and, in the back of the room, two tables of school district administrators. All face tough questions about Tosa's middle schools and high schools — which of those buildings will remain open, which might close or be converted to new use, which will need millions of dollars in upgrades — and the underlying uncertainty of whether voters will accept a capital referendum large enough to ensure Wauwatosa's children are taught in facilities that meet the community's expectations for public education.

The parents are serving on a district body known as the Secondary Schools Ad Hoc Committee, which since May has been tasked with studying Tosa's school buildings, comparing them to other districts in the state and then reviewing seven proposed options for reconfiguring Tosa's facilities that would be expensive, disruptive or both.

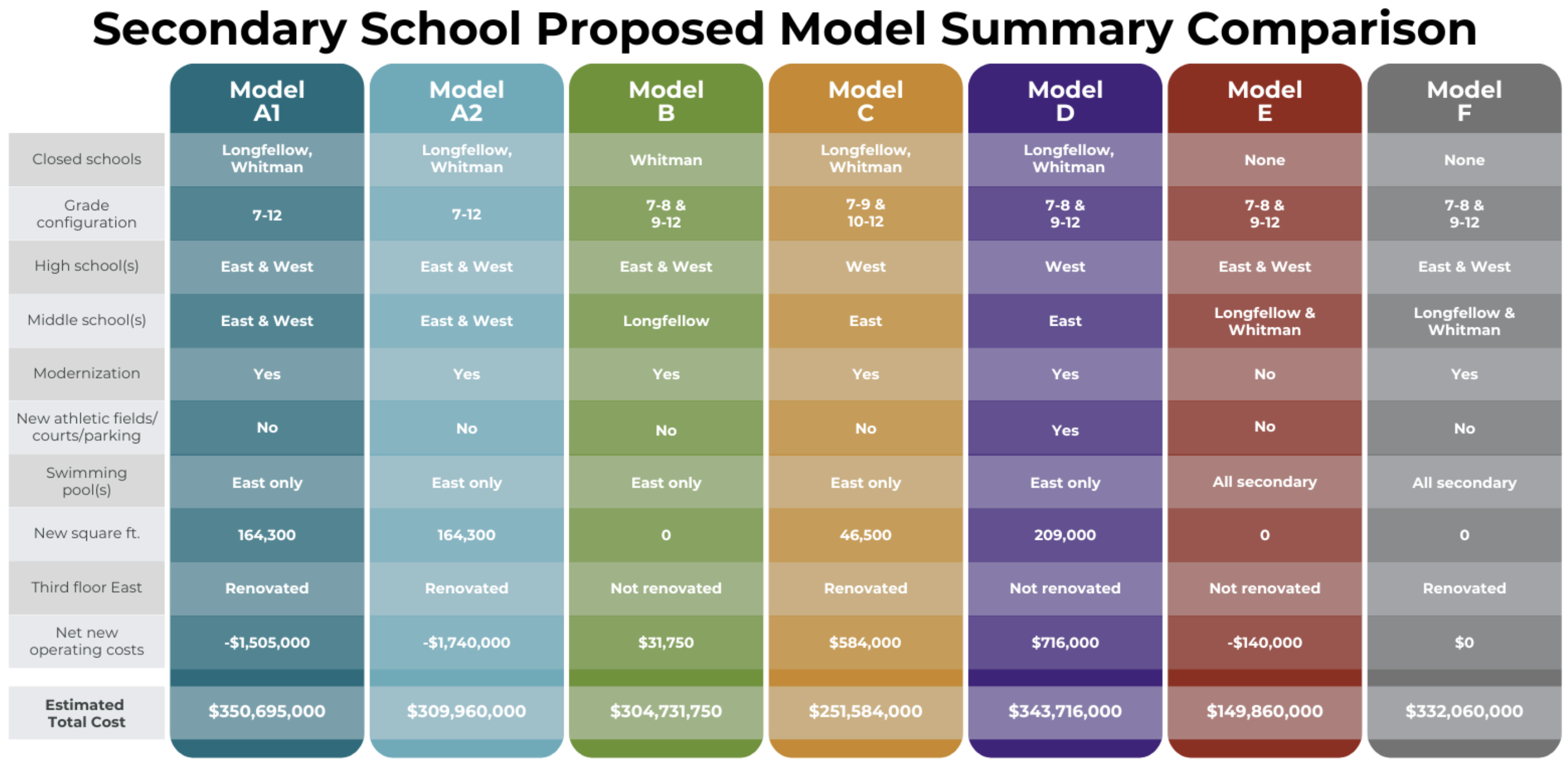

All options assume the district will move sixth-graders from the middle schools to elementary schools. Five of the seven options involve closing one or both middle schools or consolidating Tosa's two high schools and two middle schools at costs as high as $350 million. The cheapest, a "status quo" option that would keep all schools open in their current configuration, would still cost district taxpayers an estimated $150 million because of deferred maintenance, particularly at the two high schools.

The committee is due to make its recommendation to the school board by the end of 2025. The school board then will share and discuss that recommendation with the community in 2026 before agreeing on a path forward that likely will include a new referendum.

"This committee has a big decision in front of them about what's the best way to offer education in the community. It's not our role to tell you how to do that," Weiss said. Rather, the city officials' presentation was informational, she said, addressing "how taxes work in the city, how development works in the city, how traffic flow and pedestrian safety work from a city perspective, just to give you guys some more information in your tool kit."

She was joined by City Finance Director John Ruggini, City Development Director Mark Hammond and City Public Works Director David Simpson, each of whom offered ways the city could help the school district if it ends up with "surplus" property at the end of this process, such as from the consolidation or closure of one or more schools.

The quality of Tosa education is not the only community interest at stake in the discussions. With identical taxing jurisdictions, both the city and the school district draw their revenue from the same taxpayers. State-imposed limits on local property tax increases are putting a pinch on the resources of cities and school districts across Wisconsin, and what Tosa does with its school facilities could have a major impact on the financial sustainability of both the city and the school district.

Ruggini emphasized that point while suggesting that both might benefit from partnerships that help reduce the cost of maintaining duplicate and excess facilities.

"I think I can safely say — and I think Scot [Ecker] would agree, your [schools] CFO — that both the city and the school district own too many buildings and too much land to maintain under the current financial structure," Ruggini said. "It's in the city's and the school district's best interest to find ways to find the right balance of long-term operating costs."

He cited the evening's meeting space as an example. The city has its own meeting rooms at City Hall, which often go unused several nights each week.

The school district also is grappling with the expense of operating and maintaining 14 primary and secondary school buildings at a time when enrollment has been gradually declining. Concerns about that expense have influenced the Ad Hoc Committee's conversations, yet Wauwatosa Schools Superintendent Demond Means also has urged the committee's members to keep their primary focus on the community's educational goals and what it would take for the school district to meet those goals.

At a previous meeting of the Secondary Schools Ad Hoc Committee, on Sept. 9, some members said they couldn't ignore that Wauwatosa voters may be feeling referendum "fatigue." A $125 million capital referendum passed in 2018 allowing the district to rebuild four elementary schools and make more modest improvements to other buildings. Then in November 2024, voters endorsed both a $60 million capital referendum and a $64.4 million operational referendum.

The most recent capital referendum was only intended to address deferred maintenance at the district's elementary schools and accessibility at all schools. The total was a fraction of what it would cost to fully modernize Tosa's secondary schools, the four middle and high schools, under any of the seven configurations the district has now identified.

"We can't ignore what the public would or wouldn't support," said Will Gilbert, a committee member representing Longfellow Middle School parents.

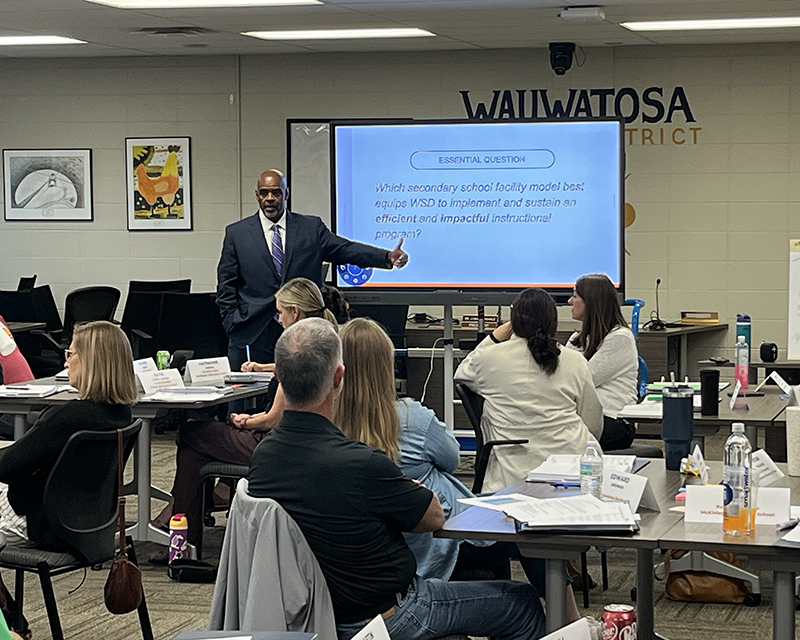

After additional discussion of the potential size and timeline of a new facilities referendum, Means, who had been sitting quietly in the back of the meeting room, stood to speak, walked to the front and drew the committee's attention to the "Essential Question," which had been scrawled in marker on a large piece of paper and also was projected onto a screen behind him.

It read: "Which secondary school facility model best equips WSD to implement and sustain an efficient and impactful instructional program?"

"We've invited you to be part of this process to answer this essential question," Means told the committee, pointing to the projected slide. "This is your committee, but my concern is that if you get inundated with trying to figure out the next four steps in the process, you will not answer this question."

Some members still pushed back, agreeing with Gilbert that they could not answer the question in a vacuum, especially if all their work might be rendered moot by making a recommendation only to see it rejected by voters.

"I think it's disingenuous to us to not focus on the fact that there's going to be some community impact on cost," Tyler Malzhan, another Longfellow parent, told Means. "I get that it's not part of this question, but that's [what] the community's going to ask us. We know that, and that's why were' here."

Means tried to assure them that he was not being disingenuous, but rather urged them to "trust the process" while acknowledging that the district has not always empowered the community in the past to think broadly about its educational goals.

"As superintendent, I believe that this community has not answered this question for decades," Means said. "And as a result of not answering this question for decades, regardless of what the price will be, we have now found ourselves in this situation."

This situation could lead to significant school closings. The district last year already raised the possibility of closing Longfellow and Whitman middle schools and absorbing those grades in the high schools and elementary schools. Of the seven models now being considered by the Secondary Schools Ad Hoc Committee, four would eliminate the middle schools and either maintain two separate high schools or create a single high school at West and convert East into a single middle school for the whole city.

Full details about the committee and the seven proposals is available here on the school district website.

The Ad Hoc Committee has been asked to reduce the seven options to five or fewer by October, when the district plans to launch a community survey about those proposals to gather broader feedback.

On Sept. 16, the City Hall officials' presentation was inspired largely by possibility that one or both of the district's middle schools could end up vacant at the end of this process and in need of redevelopment.

Hammond, the city's development director, said he and other city officials would be available to support the district if it were to pursue redevelopment. The city has its own goals, as outlined in its comprehensive plan, which include increasing the tax base and adding more housing units.

"There's also a community interest that could come into play," Hammond said, such as the creation of parkland or other open space. The city could also help the school district navigate the rezoning process for a former school property, as well as the mix of incentives and conditions that might produce a worthwhile agreement with a prospective developer.

Weiss also emphasized that Wauwatosa's latest comprehensive plan, updated in February, references this kind of collaboration with the school district "to identify underutilized or disused spaces for potential reuse for community programs or redevelopment opportunities."

"It's one of the main reasons why we're talking with you today," she said.

She also underscored that City Hall and the Wauwatosa School District share the same constituents, and while parents and school leaders are considering what is best for the school district, city leaders are available to "provide some technical expertise."

- David Paulsen, a Tosa East Towne resident and editor of Tosa Forward News, has more than 25 years of experience as a professional journalist. He can be reached at editor@tosanews.com.